The Tour de France is one of France’s most lauded sporting events. It is a huge presence in the memory and identity of many French people and those from farther afield. The retracing of old routes, the blanket media coverage and the sense that it “belongs to the French collective memory of the Twentieth Century” all place it on the pantheon of international sporting events.[1] A symbol of French national identity, it communicates endurance, a connection to the landscape of France, and a tradition that speaks to the rest of the world. In many ways, it is a fantastic symbol of enduring French cultural exceptionalism, even if it has been dominated by riders from outside of France in recent years. As such, has often been the target for political protests.[2] This blog looks at the 2007 tour, and a tragedy that was narrowly avoided in the winelands of the South.

The 2007 Tour was won by Alberto Contador, the Spaniard with a glittering array of medals and a chequered reputation for doping. Yet, it will be remembered more readily for its association with mad-dogs and Englishmen. It began in London, with a prologue leg promoting cycling and French culture across the Channel. As described by the Tour:

“On Saturday 7th July 2007, starting on Whitehall, in front of Trafalgar Square, the riders will race past Downing Street towards Parliament Square on an 8 km course. Turning at the Houses of Parliament, the route goes along Victoria Street, past Westminster Abbey and in front of Buckingham Palace. After the Palace the riders will pass through the middle of Wellington Arch, before looping through London’s most famous park, Hyde Park. Finally the riders will pass back around Hyde Park Corner and along Constitution Hill, before ending on The Mall with Buckingham Palace as a backdrop.”

Of note during the race was the overwhelmingly odd sight of dogs entering the course and causing collisions on two separate occasions. The first saw Marcus Burghardt strike a large Golden Labrador which wandered across the track during Stage 9. The dog was unharmed, and the rider suffered only cuts and bruises. After replacing a buckled wheel, he was back on his way. At Stage 18, Sandy Casar and Frederick Willems were involved in another collision with a dog, this time a Brown Labrador. The dog got up and ran away, apparently unharmed, though Willems and Casar were more badly hurt with gashes and bruises.

Yet, there could have been a markedly more serious event at Stage 14, between Mazamet and Plateau-de-Beille, as the riders approached the Pyrenees.

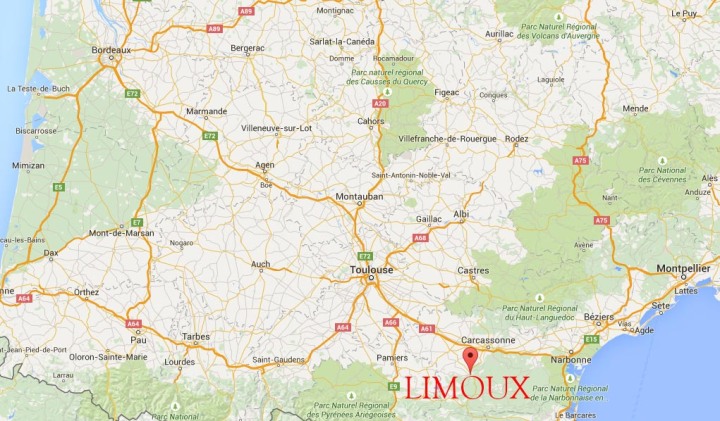

At the round-about by the Leclerc shopping centre, in the town of Limoux, lay a surprise for riders. A home-made bomb made by winegrowers desperate to draw attention to their plight. Luckily, a call to police alerted them to the device, which was removed before riders arrived. On 25 July 2008 a 34 year old winegrower called Jérôme Soulère was arrested by police at his house in Malviès, in the Limoux. Soulère was charged with possessing bomb-making material after an accident in his cellar left him badly injured. Materials found in the cellar matched those used in incidents previously linked to the CAV d’Aude, a local branch of the winegrowers’ action committees.[3] Police accused him of having participated in previous attacks, namely the bombing of a tax-office just south of Carcassonne in 2006, and a threat to plant a bomb in 2007 when the Tour de France passed through the town of Limoux.[4]

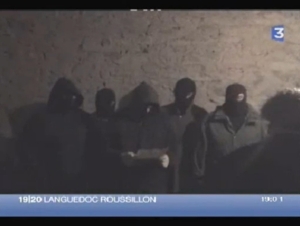

On the attempt to destroy the tax office, Soulère claimed that their goal was “to make heard the blows being dealt to winegrowers and ensure the media cover them.” Likewise, his bomb-threat during the Tour de France was intended not to explode and cause damage but to raise awareness of the plight faced by winegrowers; he alerted police of the device’s location in advance and left alongside it “a document detailing the demands of the winegrowers.”[5] Greater restrictions to prevent fraud, controls on imports, and guaranteed minimum prices for French wine: these demands were the traditional refrain of winegrowers, speaking on the centenary of the Grand Revolt of 1907. This huge, movement right across the Midi had seen an estimated 600,000 gather in Montpellier at the culmination of a vast series of protests that looked at times like some sort of regional revolution. I have written recently on the political contours of that Revolt in Modern and Contemporary France, with a co-authored article entitled ‘From the soil we have come, to the soil we shall go and from the soil we want to live’: Language, Politics and Identity in the Grande Révolte of 1907. A century after this high watermark, militant winegrowers sought to make their presence felt once more and capitalise on the centenary. They made videos demanding the government intervene to support their cause, warning about the fact that blood could flow if they were forced from the land.

Wearing balaclavas and issuing demands, this was a frightening moment for many, and seemed out of touch with the idea of wine, usually discussed in the language of luxury. Yet, as these winegrowers reminded, wine had long been a space for protest, rhetoric and violence. A long history of mobilisation and difficult relations with authorities had seen them involved in a number of high-profile, shocking events. This is precisely the story I am currently writing about in a book I’m preparing for Manchester University Press, Terror and Terroir: The Winegrowers of the Languedoc and Modern France. After the death of a winegrower, and a policeman in a shootout in 1976 near Narbonne, and the firebombing of an enormous supermarket in Carcassonne in 1984, this bombing was a potential tragedy in the making. That the police were informed ensured it was ultimately averted, though it created a dangerous moment.

Interestingly, the bombing brought out another aspect of the 1907 Revolt, as covered in my article that I previously linked: the importance of regional identity, and of the Occitan language. During his arrest and the investigation into his actions, Soulère received support from the militant Occitan movement Anaram Au Patac (a self proclaimed revolutionary movement of the Occitan left- you can see one of their videos HERE)[6], who cast him as a “victim of his engagement with the winegrowers’ cause.” This was, to an extent, a revival of the grand social alliance which had characterised the strongest moment of winegrowers and Occitan nationalists in the 1970s, before the stain of spilt blood and grand political shifts shattered their appeal. Yet the profile of the Occitan group and the nature of their solidarity were expressive of not only the distance the winegrowers’ groups had fallen, but also the calibre of their fellow-travellers in such extreme methods. Anaram expressed solidarity with the struggling Midi wine industry and condemned industry figures who spoke out against Soulère as “subject to the statist domination of Paris”.[7] In supporting these actions both the CRAV and Anaram placed themselves on the wrong side of history. Both sought to communicate something from that huge revolt in 1907, and both failed to find its relevance.

In a small moment like this, we can see many of the issues I’m writing about in my book. This moment of national celebration verged on a terrain which fostered resentment below the national level. On the centenary of an event that winegrowers felt communicated their misery and their fury, the re-emergence of violent rhetoric was shocking. These symbols of regional identity, the Occitan Language and Languedocien wine, were used as weapons against the state, during an event that is one of its most dearly held national and international celebrations. A race that started in London came perilously close to tragedy in France’s wine heartlands. Clashing symbols show us how important it can be to understand the context of contestation. Far beyond a moment of typical ‘French’ protest, this was part of a much larger story, with its own scars and bitter resentments. From a tour which seemed destined to be dominated by mad-dogs and Englishmen after two accidents and a Grand Départ, it was instead a reminder of clashing national symbols and lingering local problems: of wine, terror and the Tour.

[1] J. Polo, ‘Ambushing the Tour for Political and Social Causes’, in Dauncey and Hare (ed), The Tour De France, 1903-2003: A Century of Sporting Structures, Meanings and Values (London: Routledge, 2004), p.263.

[2] See Polo’s aforementioned chapter.

[3] ‘Malviès. Le jeune vigneron testait des explosifs’, La Dépêche 25/07/2008 .

[4] ‘Jérôme Soulère avoue des attentats’, La Dépêche 26/07/2008.

[5] ‘Carcassonne. Il avait fait sauter la perception : 6 mois de prison’, Dépêche du Midi 03/12/2009.

[6] Anaram Au Patac were formed in 1992 in Pau and had 3 regional presences in Bordeaux, Clermont-Ferrand and Montpellier. They published a review called ‘Har/Far’ and survived until 2009, when on the 19 September they joined with Combat d’Oc to form a new revolutionary Occitan Party, Libertat.

[7] Anaram Au Patac communiqué, 12/08/2008 [http://occitania.forumactif.com/quiosc-f25/solidaritat-vinhairons-t867.htm][Accessed: 27/10/2010].

2 thoughts on “Wine, Terror and the Tour de France”